The Civil Rights Act is Unconstitutional and Hurts Minorities

The notion of “civil rights” seems to play a continuously persistent role in politics.

Whether it involves voting rights for African Americans in the 1960s or whether a religious Christian must serve a homosexual couple against their will, the issue that comes into mind is that of civil rights.

However, many are unclear about what civil rights even are. This leads to three questions:

- What are civil rights?

- Was Civil Rights legislation necessary to ensure “equality”?

- Can one simultaneously be constitutionalist and egalitarian?

The terms “civil rights” and “civil liberties” are often used interchangeably among the general public. The notion that the two terms mean and advocate the same thing is, however, a great misconception. Civil liberties, defined as the constitutional protection of individuals against the government, aim to do exactly that – protect people from the potential of government overreaching. Civil rights, however, are the protection of minority, underprivileged, or underrepresented groups from discriminatory treatment. Despite their now-evident differences, there can be overlap between the two. For instance, constitutional civil liberties, in the form of various amendments, such as the 24th Amendment, which outlawed the use of poll taxes, previously used to prevent African Americans from voting, are obviously intertwined with the efforts of civil rights movements. However, such coinciding is rarely the case. With increasing frequency, newly enforced civil rights legislation is not only distancing itself from, but also even directly contradicting with constitutional civil liberties once granted to the people.

“Equality”

The intent of civil rights is to advocate equality. However, there are many implications within and interpretations of the word “equality”. The three key definitions of equality include legal equality (equal treatment under the law), equality of opportunity (creating a “level playing field”), and equality of outcome (assistance to previously disadvantaged groups, with the intent of ultimately creating equal economic outcome).

Legal Equality

Legal equality parallels and poses no threat to constitutional civil liberties. Through the growth of civil rights movements, equality before the law has grown into a right granted to all Americans. The Civil War Amendments (Amendments 13, 14, and 15) are examples of the overlap of civil rights and civil liberties. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, legally ending the status of some human beings as property.  The 14th Amendment, which is best known for establishing equality before the law, in part states that, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of the citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”. Through this clause, the 14th Amendment essentially established legal equality; however, despite it being written in print, legal equality was not guaranteed until nearly a century later. Another notable aspect of the 14th Amendment is that it not only established legal equality at a federal level, but at a state level as well. This fact has allowed the Supreme Court of the United States to ensure that legal equality is guaranteed by state governments as well as by the national government.[1]

The 14th Amendment, which is best known for establishing equality before the law, in part states that, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of the citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”. Through this clause, the 14th Amendment essentially established legal equality; however, despite it being written in print, legal equality was not guaranteed until nearly a century later. Another notable aspect of the 14th Amendment is that it not only established legal equality at a federal level, but at a state level as well. This fact has allowed the Supreme Court of the United States to ensure that legal equality is guaranteed by state governments as well as by the national government.[1]

The 15th Amendment further ensured legal equality by declaring that a citizen’s right, “… to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude”. This established the right to vote and legal participation for people of any race; however it continued to be infringed until the passing of the 24th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 24th Amendment outlawed requiring taxation prior to allowing one to vote – a method used by various states to prohibit African Americans from voting. Though not an amendment, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 furthered legal equality by ending race-based voter “tests”, therefore, allowing people of all races to be represented when voting on decisions and politicians.

Another amendment tied to legal equality is the 19th Amendment, which basically parallels the 15th Amendment, except that it takes into account biological sex rather than race. Though, similarly to the 15th Amendment, some states did permit women to vote prior to its passage, the 19th Amendment nationalized the voting right for female voters, allowing females in all states to have voting rights.

Equality of Opportunity

Equality of opportunity is, in simple terms, allowing people access to the same opportunities no matter what their gender, race, religion, ethnicity, or sexuality may be. These opportunities are not related to the enforcement of laws and voting rights as in the case of legal equality, but rather, tend to pertain to education, business, and personal affairs. Civil rights movements contributed greatly to the growth of equal educational opportunity, through the form of various important court cases. The well-known court case Brown v. Board (1954), ruled that, “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and therefore declared de jure segregation (segregation by law) unconstitutional. The decision on this ruling not only impacted public schools, but also eventually grew to impact all public and private facilities in which state governments implemented de jure segregation. Not surprisingly, Southern state governments were unwilling to budge until a later Supreme Court case, Alexander v. Holmes County (1969), demanded an immediate end to educational segregation.

Contrary to some misperception, the required end to per jure segregation, whether in a private or public atmosphere, is not unconstitutional. Why? By definition, per jure segregation is segregation implemented and enforced by the government. This means that under per jure segregation, private business owners were not refusing service to certain customers out of their own desire, but rather because their state governments demanded them to. They were abiding by government laws, preventing their ability to serve all customers, but rather, only cater to a specific race. The central government declaring per jure segregation illegal, therefore, helped business owners rather than hurt them, as it removed prior gubernatorial restrictions, which only allowed business owners to cater to specific race.

So where does all the controversy regarding the constitutionality of segregation and desegregation arise? The answer is de facto segregation, which is basically segregation that was not being enforced by any government or laws but occurring merely by the will of individuals and business owners. Subsequent to the overturning of per jure segregation, civil rights groups pushed for the government-enforced ending of de facto segregation. It is in this regard that the government enforcement of “equality of opportunity” could be considered unconstitutional. Not only did the central government constitutionally end previously enforced racist state laws, but also chose to extend their power to unconstitutionally govern the decisions of private businesses and individuals.

This can be seen most clearly in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed voluntary discrimination (by choice of the store owner) based on race, religion, gender, or ethnicity.

The constitutionality of this law comes into question when considering where in the constitution power was possibly given to the central government to deny individuals the right to freedom of association in private business.

(The freedom of association is a right not explicitly stated in the Constitution; however, it is included within the penumbra of the “Freedom of Assembly” clause within the First Amendment. Such was established by various notable Supreme Court cases, the most recent being the case, Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000), within which the notion of freedom of association was referred to in ruling that the Boy Scouts of America was allowed to remove troop leaders from the association for being homosexual.)

The central government referred to the Commerce Clause within the Constitution and the early 19th century Supreme Court ruling, Gibbons v. Ogden. This ruling merely allowed for the central government to regulate interstate commerce by reaffirming the Commerce Clause, which, in part, stated that, “The Congress shall have Power To… regulate Commerce with foreign Nations and among the several States”. The central government has abused the Commerce Clause multiple times in the past, and it was no different when regarding civil rights legislature. It was unfairly and inaccurately declared that any business with more than twenty-five employees must engage in interstate commerce. Therefore, the government declared that it had the power to control the affairs of private businesses with more than 25 employees and implement the Civil Rights Act upon them, fining them or closing their business if they refused service based on racial and other similar factors.

Equality of Outcome

Despite evident government efforts to end both per jure and de facto segregation, de facto segregation continues to persist to this day.

One major form of self-segregation is the existence of racial enclaves, neighborhoods within a city where one race is very dominant. Originally, this was a result of restrictive covenants, agreements in which white homeowners within a neighborhood agreed not to sell to people of color. However, this was addressed by the Supreme Court Case, Shelley v. Kramer (1948), which declared restrictive covenants to be unconstitutional. Unsatisfied with the outcome of the ruling, the central government passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which declared that property owners and sellers could not refuse to sell or rent property based on the race of the potential future owner. This restriction of an individual’s freedom to choose their potential customers was not based on any part of the Constitution, and was instead based off of the ruling of the Kramer case. Despite both these efforts, in large and small cities alike, people of different races tend to self-segregate, voluntarily choosing to live among individuals who share the same cultural backgrounds. However, an economic trend was found in this self-segregation, noting that people from European (and Asian) background tended to live in more expensive homes and wealthier neighborhoods than African Americans (and people of Hispanic background).

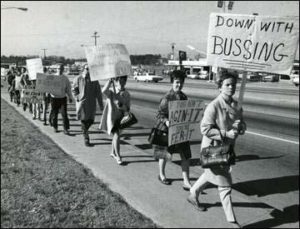

In order to reach racial economic equity (equality of outcome), the Supreme Court declared in Swann v. Charlotte (1971) that district courts could order busing to integrate schools. This meant that courts could order that students could be involuntarily bused miles away, out of their neighborhoods, hoping to create racial diversity within public schools and to create “equal educational opportunities”. While this was an occurrence exclusive to public schools, it was often done involuntarily and against the will of not only white students, but African American and other students of color as well, as it grew quite difficult to accommodate distant bus rides to schools. Furthermore, while wealthy students had the option to attend public schools to avoid busing issues, economically disadvantaged students, many of whom were students of color, did not, and had to continue enduring bus rides to distant schools, where not only were they often subject to poorer academic performance and inability to participate in after school activities due to the time wasted by distant busing, but also often isolated, separated from their friends and communities.

The ultimate unconstitutional and invasive attempt to establish equality of outcome can be found in the notion of affirmative action in education. Primarily, many public and state universities had a quota system, under which they admitted a certain number of people of a specific race, despite their academic merit. Under this system, white (and Asian) students who were more merited than most or all admitted non-white students could be denied on a basis of race (the fact that they were white) alone, because the quota allocated a certain number of seats to nonwhite students.

This brought up the argument of reverse discrimination, which declared that qualified white students were being denied their deserved admission on the basis of the fact that they were white. This quota system was challenged by Mr. Bakke, a white medical student who had higher MCAT scores than all minority students admitted under the quota system and was denied admission to University of California Davis. He took the issue to the Supreme Court, where required quota systems were finally declared unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. Despite this ruling, the Court declared that schools with a history of discrimination were still allowed to impose quotas. They also stated that race was still to be taken as a factor for admission if not under a quota system. Therefore, some colleges adopted a point system, under which additional “points” were given to minority students. The University of Michigan assigned nearly twice as many points to the fact that an individual was not white than to a perfect SAT score or GPA. This issue was challenged in the Supreme Court case, Gratz v. Bollinger (2003), where it was determined that such an extreme point system equated to a quota system and continued to maintain the opinion of the Regents v. Bakke (1978) ruling. In the modern day, while quota systems are unconstitutional, affirmative action in a less extreme sense is not, and continues to be practiced by the admissions offices of various universities throughout the nation.

Conclusion

Legal equality is doubtlessly constitutional. The amended Constitution guarantees equal treatment under the law to all American citizens no matter what their race, religion, gender, sexuality, or ethnic background may be. Equality of opportunity is constitutional when regarding the public sector and when the individual rights of private businesses are not infringed. While I, personally, would never discriminate on race (ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc.) nor would I support a business who did so, it is evident that the central government overreached in its abuse of the Commerce Clause to implement private anti-discrimination laws. I personally believe that individual preferences and free market competition would harm the business of racist businesses refusing to serve minority groups, forcing them to change their preferences or to go out of business[2] and if desegregation laws were to be implemented, it would be preferable if they were done so at a state or more localized level as to not violate the Constitution. Equality of outcome legislature, in nature, inhibits the opportunities and freedoms of more privileged groups in order to pull-up (for lack of a better term) underprivileged groups. This inherently contradicts the idea of legal equality and the 14th Amendment, as it is an example of government entities abridging the privileges of more successful individuals in order to uplift previously disadvantaged ones.

Due to this, the term egalitarian is controversial in definition. To believe that all humans deserve equal legal rights (something guaranteed by the Constitution) is not identical in believing in equity, or the implementation governmental policies in order to create “equality of outcome”. Government-established equality violates individual freedoms, and quoting whoever who said it first, “free people are not equal and equal people are not free”.

[1] Marriage (interracial and homosexual) will be addressed in a later essay regarding marriage, sex, and abortion laws and the “right to privacy”.

[2] This will be addressed in a later essay regarding the effects of free-market capitalism regarding racism and discrimination in private business.